Bees may seem like uninvited guests at your picnic -- but before you shoo them away from the fruit salad, think twice, as they play a critical role in making your picnic possible.

Some of the most healthful, picnic favorites -- from blueberries, strawberries, cantaloupe, watermelon, cucumber, avocados, to almonds -- would not make it to the table without the essential work by insects and bees.

Most crops depend on pollinating insects to produce seeds or fruits. In fact, about three-quarters of global food crops require insect pollination to thrive; and one-third of our calories and the majority of critical micronutrients, such as vitamins A, C and E, come from animal-pollinated food crops.

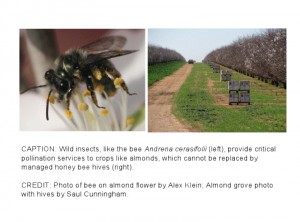

To provide pollination services to such crops, farmers often rely on domesticated honey bees. But with the decline of honey bee colonies due to diseases and pesticides, this single-management strategy is increasingly risky. Moreover, a recent study in the journal Science, led by Lucas A. Garibaldi (at the National University of Rio Negro in Argentina) involving myself and 48 other scientists, indicates that reliance on a single domesticated species is not only risky, but also inefficient.

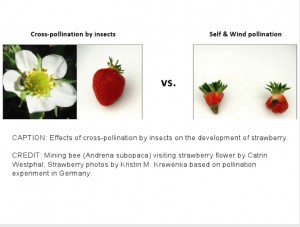

Based on a synthesis of 600 fields at 41 crop systems, we found that wild bees and insects were more effective at pollinating than managed honey bees, even doubling the proportion of flowers that develop into mature fruits or seeds. In fact, the proportion of flowers that matured to fruit improved in every field visited by wild insects, compared with only 14 percent of fields visited by honeybees. This means that rented honey bees supplement, rather than replace critical, yet free pollination services provided by wild bees to crops.

This is a big deal. As the world population is estimated to increase to nine billion by 2050, with a corresponding need to double the global food supply, we must find ways to make more food from the same amount of land. And our research suggests that to achieve such "sustainable intensification" we should secure healthy populations of wild pollinators across agricultural landscapes worldwide. But given dramatic declines in many bee species globally, this presents a daunting yet timely challenge.

A major driver behind the decline of wild pollinators is the loss and degradation of natural habitats. Simultaneously, farm management practices have been implicated. To better understand these different factors, Claire Kremen (at University of California, Berkeley), Eric Lonsdorf (previously at the Lincoln Park Zoo, Chicago), and I worked with an international team of bee biologists and synthesized data on wild bee communities in agro-ecosystems from around the globe (including 39 studies on 23 crops in 14 countries and 6 continents).

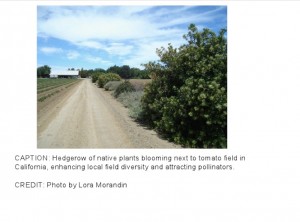

We found that wild bee assemblages were most diverse and abundant on fields managed organically and that grew a variety of crops or had natural vegetation like hedgerows, flower margins, and live fences (as recently published in Ecology Letters).

Our results suggest that switching from conventional to organic farming could lead to an average increase in wild bee abundance and richness by 74 percent and 50 percent respectively, and enhancing field diversity could lead to an average 76 percent increase in bee abundance. Farmers can therefore maximize pollination services to their crops by reducing their usage of bee-toxic pesticides and herbicides, planting small fields of different flowering crops, increasing the use of mass-flowering crops in rotations and breaking up crop monocultures with hedgerows and other natural vegetation.

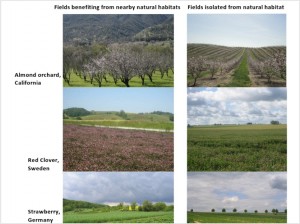

In addition to local-scale field effects, we modeled landscape-level effects using a crop pollination model (available through the Natural Capital Project), and found that bees benefited when farms were surrounded by natural habitats, especially when in large monocultures; and that each 10 percent increase in the amount of high-quality bee habitats in a landscape leads to an average 37 percent increase in bee abundance and richness.

Orchards and fields surrounded by natural or semi-natural habitats (left) versus those that are more isolated (right). Wild bees are more abundant and diverse on fields closest to natural habitats. Almond photos by Alex Klein and Claire Brittain; Red clover photos by Maj Rundlöf; Strawberry photos by Catrin Westphal.

This is good news. This means we have multiple options to safeguard pollinators and their services to crops. We can protect and enhance natural areas around farms as well as improve on-farm management to benefit both our natural heritage and our agricultural harvests.

So if bees at a picnic may not sound like fun, believe me, you couldn't have one without them.